With apologies once again to Rogers and Hammerstein, here are my top 10 favorite things (book-wise) from 2011. I have restricted myself to books reviewed here at The Fourth Musketeer. The books are presented in no particular order. Please note: these are not necessarily the books I think are "best" (whatever that means!) but rather books that I found personally compelling for one reason or another.

Young Adult

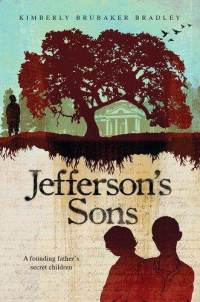

Jefferson's Sons: A Founding Father's Secret Children, by Kimberly Brubaker Bradley (Dial Books for Young Readers). A fictionalized look at life at Monticello through the eyes of three of his slaves, two of whom were his sons by his slave mistress, Sally Hemings.

Between Shades of Gray, by Ruta Sepetys (Philomel). In 1941, 15-year old Lina, her mother, and brother are taken from their Lithuanian home by Soviet guards and sent to Siberia, where her father is sentenced to death in a prison camp while Lina fights to survive. Based on the author's own family history.

The Berlin Boxing Club, by Robert Sharenow (Harper Collins). In 1936 Berlin, 14-year old Karl Stern, considered Jewish by the government despite a non-religious upbringing, learns to box from the legendary Max Schmeling while struggling with the realities of life as a Jew in Nazi Germany.

Tween/Middle Grade

Saving Zasha, by Randi Barrow (Scholastic). In 1945 Russia, those who own German shepherds are considered traitors, but Mikhail and his family are determined to keep the beautiful dog a dying man brought them, while trying to keep the secret from Mikhail's nosy classmate Katia.

Inside Out and Back Again by Thanhha Lai (Harper). In free verse poems, a young girl chronicles the life-changing year of 1975, when she, her mother, and her brothers leave war-torn Vietnam to resettle in Alabama.

Picture Books

For the Love of Music: The Remarkable Story of Maria Anna Mozart, by Elizabeth Rusch (Triangle Press). A lovely picture book biography of the sister of the famous composer.

These Hands, by Margaret H. Mason (Houghton Mifflin). Combines a little known piece of labor history and the civil rights movement with a tender portrait of a grandfather’s relationship with his grandson.

Narrative Non-Fiction

Flesh and Blood So Cheap, by Albert Marrin (Knopf Books). 2011 marked the 100th anniversary of the Triangle Fire, the worse disaster in American labor history, and Marrin brings the tragic events of that spring afternoon to life, setting the fire in a sweeping historical narrative encompassing not only the events leading up to the fire, but what happened afterwards.

Tom Thumb: The Remarkable True Story of a Man in Miniature, by George Sullivan (Clarion Books). The fascinating story of the little person Charles Stratton, “discovered” by P. T. Barnum at the tender age of four; Tom Thumb was one of our nation’s first true celebrities.

Young Adult

Jefferson's Sons: A Founding Father's Secret Children, by Kimberly Brubaker Bradley (Dial Books for Young Readers). A fictionalized look at life at Monticello through the eyes of three of his slaves, two of whom were his sons by his slave mistress, Sally Hemings.

Between Shades of Gray, by Ruta Sepetys (Philomel). In 1941, 15-year old Lina, her mother, and brother are taken from their Lithuanian home by Soviet guards and sent to Siberia, where her father is sentenced to death in a prison camp while Lina fights to survive. Based on the author's own family history.

The Berlin Boxing Club, by Robert Sharenow (Harper Collins). In 1936 Berlin, 14-year old Karl Stern, considered Jewish by the government despite a non-religious upbringing, learns to box from the legendary Max Schmeling while struggling with the realities of life as a Jew in Nazi Germany.

Tween/Middle Grade

Saving Zasha, by Randi Barrow (Scholastic). In 1945 Russia, those who own German shepherds are considered traitors, but Mikhail and his family are determined to keep the beautiful dog a dying man brought them, while trying to keep the secret from Mikhail's nosy classmate Katia.

Inside Out and Back Again by Thanhha Lai (Harper). In free verse poems, a young girl chronicles the life-changing year of 1975, when she, her mother, and her brothers leave war-torn Vietnam to resettle in Alabama.

Picture Books

For the Love of Music: The Remarkable Story of Maria Anna Mozart, by Elizabeth Rusch (Triangle Press). A lovely picture book biography of the sister of the famous composer.

These Hands, by Margaret H. Mason (Houghton Mifflin). Combines a little known piece of labor history and the civil rights movement with a tender portrait of a grandfather’s relationship with his grandson.

Narrative Non-Fiction

Flesh and Blood So Cheap, by Albert Marrin (Knopf Books). 2011 marked the 100th anniversary of the Triangle Fire, the worse disaster in American labor history, and Marrin brings the tragic events of that spring afternoon to life, setting the fire in a sweeping historical narrative encompassing not only the events leading up to the fire, but what happened afterwards.

Tom Thumb: The Remarkable True Story of a Man in Miniature, by George Sullivan (Clarion Books). The fascinating story of the little person Charles Stratton, “discovered” by P. T. Barnum at the tender age of four; Tom Thumb was one of our nation’s first true celebrities.